It sounds like a sci-fi movie, but an Adelaide scientist is leading a global mission to grow plants in space for the first time – and the breakthroughs could also supercharge sustainable agriculture on Earth.

When it comes to growing food in space, most people picture Matt Damon in The Martian, “sciencing the shit” out of potatoes on Mars.

Professor Matthew Gilliham doesn’t mind the comparison – in fact, he calls the movie “brilliant” and gives the general idea of growing plants on Mars a “big tick”. But while The Martian was all red dust, duct tape and potatoes, the real story of space farming is unfolding in high-tech labs right here in Adelaide.

As Director of the ARC Centre of Excellence in Plants for Space (P4S), based at the University of Adelaide’s Waite campus, Professor Gilliham is leading one of Australia’s most ambitious science missions: figuring out how to keep humans alive, fed and healthy on the Moon, Mars and beyond – while helping us grow food more sustainably back here on Earth.

Life support, powered by plants

“Plants are essential for life on Earth – and beyond Earth,” Professor Gilliham explains. “They give us oxygen, absorb carbon dioxide, produce our food, medicines, clothing – almost everything. They’re incredibly efficient – small seeds expand thousands of times into what we eat or use. They’re the ultimate life-support system.”

But there’s one big problem: plants did not evolve to grow in zero gravity.

In space, water doesn’t drip or flow – it clings. “Water becomes sticky and creepy,” says Professor Gilliham. “It wraps around the roots and leaves, suffocating them so they can’t get the oxygen or CO₂ they need.”

That’s why even watering plants becomes a major engineering challenge once you leave our Earth’s atmosphere.

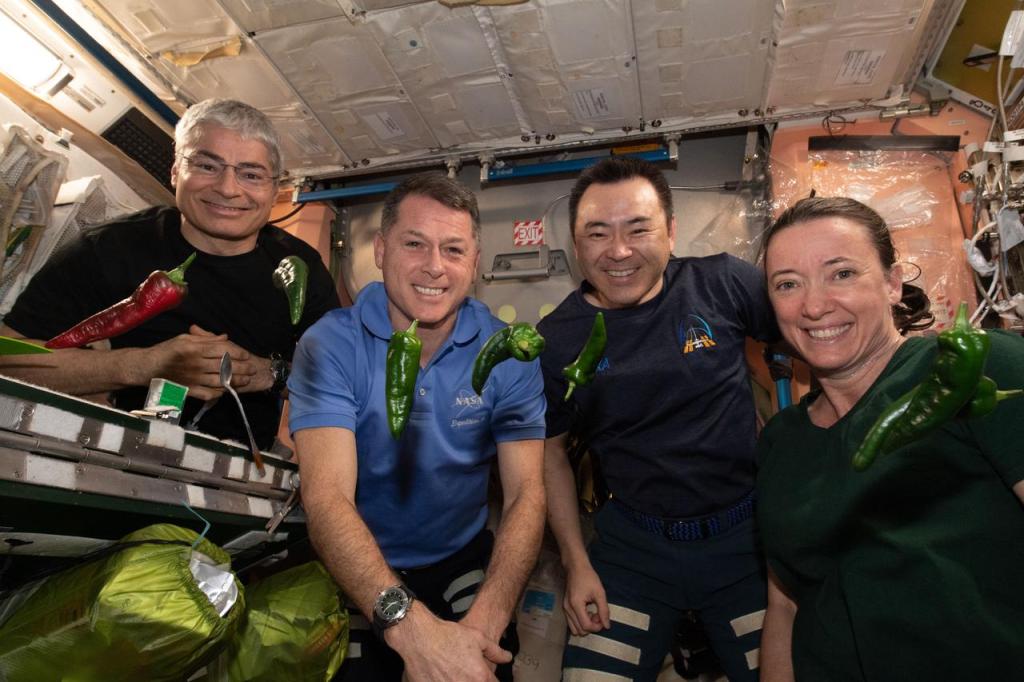

On the International Space Station, astronauts grow small crops inside ‘Veggie’ units – tending to tiny “growth pillows” filled with a clay-like medium that holds moisture around the roots. It works for small plants like lettuce and chilli peppers, but it’s far from scalable.

The first plants on the Moon

That’s where South Australia comes in. Plants for Space – working with NASA, the Australian Space Agency, universities and industry around the world – is part of a team designing a lunar plant experiment for the Artemis III mission, which launches next September, returning humans to the Moon for the first time in more than 50 years.

“It’ll be the first time plants have been grown and brought back from the Moon,” Professor Gilliham says. “That’s pretty cool.”

The experiment, called the LEAF project (Lunar Effects on Agricultural Flora), will see astronauts deploy a small, solar-powered growth chamber on the lunar surface. Inside it, plants will grow under LEDs for around ten days before being chemically “fixed” for return to Earth for analysis.

The team wants to understand how plants respond to lunar gravity – one-sixth of Earth’s – and intense radiation from the Sun.

“We’ve simulated parts of those conditions in labs here in Adelaide using machines called clinostats that mimic reduced gravity, but you can only learn so much that way,” he says. “The only real way to know is to grow them there.”

How off-planet farming really works

Unlike farming on Earth, plants grown beyond our planet won’t sit in soil or sunlight. “We’ll be using systems found in vertical farming – controlled environments with LED lighting and hydroponic nutrient films,” Professor Gilliham explains.

The goal is to create sealed habitats where every drop of water and molecule of carbon dioxide is recycled, and growth can be precisely tuned for nutrition and speed. “In space, you need to reuse everything,” he says. “It’s about efficiency and resilience.”

As for Mars, that means no dusty potato patches any time soon.

“Regolith – the dust that covers the Moon and Mars – is like shards of glass that damage roots and hold no nutrients,” he says. “On Mars it also has toxic compounds called perchlorates, so growing directly in that soil would be impossible until we work out how to clean it.”

The human side of space plants

For astronauts, plants are about much more than calories – they offer something deeper: connection.

Astronauts on the International Space Station have spoken about the joy of caring for their small gardens – nurturing life in the void, tasting something fresh and green.

“They loved it,” Professor Gilliham says. “They grew chillies and put them on everything. It’s that crunch, that reminder of Earth… The main benefits are psychological rather than nutritional until we learn how to grow more plants.”

When humans finally live on the Moon or Mars, those small patches of green could mean everything.

Why it matters on Earth

Not everything about this work is otherworldly. The same challenges that make growing plants in space difficult – limited water, poor soil, and extreme environments – are the same problems we face here on Earth.

“If we can grow food on the Moon or Mars, we can grow it anywhere in South Australia.”

That includes drought-prone regions, outback communities and remote research stations – even urban “container farms” bringing fresh produce closer to cities.

Controlled-environment agriculture – where light, temperature and humidity are perfectly tuned – can produce up to 50 times the yield of traditional farming while using far less water, at any time of year.

What space science gives back

“As we go further into space, we’re forced to think differently – to recycle everything, reuse everything, and make what we need locally,” he says. “That mindset is exactly what we need for sustainability here on Earth.”

The ripple effects of space innovation are already everywhere. “There’s been a catalogue of thousands of technologies that have spun out of space research – from camera phones to LEDs in horticulture,” Professor Gilliham says.

“When we go somewhere new, we get to decide how we’ll live differently. Space makes us rethink our footprint – how we produce, recycle, and take care of life. It gives us the chance to pause, reflect, and redo things better here on Earth.”

Professor Gilliham’s own background is in crop resilience: he’s spent decades improving drought and salinity tolerance in wheat, barley, tomatoes and grapevines. Now, those lessons from the paddock are being applied to futuristic, climate-proof food systems.

“It’s about growing smarter plants that thrive in controlled environments, that use less water and produce high-quality food all year round,” he says. “It gives us another option, especially for extreme conditions.”

Space-age innovation, South Australian roots

The research taking place in Adelaide is shaping the future of space agriculture – from the design of lunar growth chambers to the genetics of plants that can thrive with minimal water or sunlight.

Headquartered at the University of Adelaide’s Waite campus, Plants for Space brings together South Australia’s expertise in plant science, engineering and controlled-environment agriculture with partners around Australia and the world.

The $100 million ARC Centre of Excellence in Plants for Space includes more than 30 collaborators – from NASA and the Australian Space Agency to Cambridge University and the University of California – but its headquarters remain firmly at Waite.

Professor Gilliham says South Australia was the obvious choice. “SA has world-class expertise in plant science, engineering and controlled-environment agriculture. We’re small enough to collaborate easily, but big enough to make a global impact.”

He’s proud that the global spotlight on plants in space also shines a light on South Australia’s research sector.

“It highlights the importance of what’s happening here,” he says. “It’s a reminder that South Australia can be a world leader in science – we’re showing the world what’s possible.”

SA Scientist of the Year finalist

It’s that combination – global vision, local impact – that’s earned Professor Gilliham a spot as a finalist for SA Scientist of the Year at the 2025 Science Excellence and Innovation Awards.

The annual awards, run by the South Australian Government, celebrate the state’s best researchers, innovators and educators working across science, technology, engineering, maths and medicine.

Professor Gilliham says it’s an honour, but doesn’t want to take the credit alone.

“It’s not about me,” he says. “It’s about the team, and the importance of what we’re doing – supporting this ridiculously difficult, amazingly inspiring human aspiration, and bringing those benefits back to Earth.”

Winners of the 2025 SA Science Excellence and Innovation Awards will be announced on Friday, 14 November, at a special Award Celebration at the Adelaide Entertainment Centre. You can learn more about the finalists here.