Organised traffickers are targeting South Australian animals – especially a common backyard lizard – as authorities call for community help to stop illegal wildlife trade.

If you grew up in SA, chances are you’ve watched a sleepy lizard trundle across a driveway.

What most people don’t realise is that this familiar backyard buddy has become the unlikely poster animal of an international organised crime industry.

Sleepy lizards – also called shinglebacks – now make up roughly half of all reptiles seized at the Australian border. They’re targeted by overseas traffickers who can sell them for thousands of dollars each. And according to Adelaide University’s Wildlife Crime Research Hub, many die long before they reach those buyers.

Katie Smith, the Hub’s Manager, says many South Australians have no idea of the scale of the crimes targeting these harmless reptiles.

“People think of [wildlife smuggling] as just a random person taking one lizard,” she says. “It’s not like that. This is organised crime. People just don’t realise this is happening in Australia.”

The backyard lizard caught in a billion-dollar trade

Globally, the illegal wildlife trade is the fourth largest organised crime sector – sitting just behind drugs, weapons and human trafficking, and worth more than $32 billion each year.

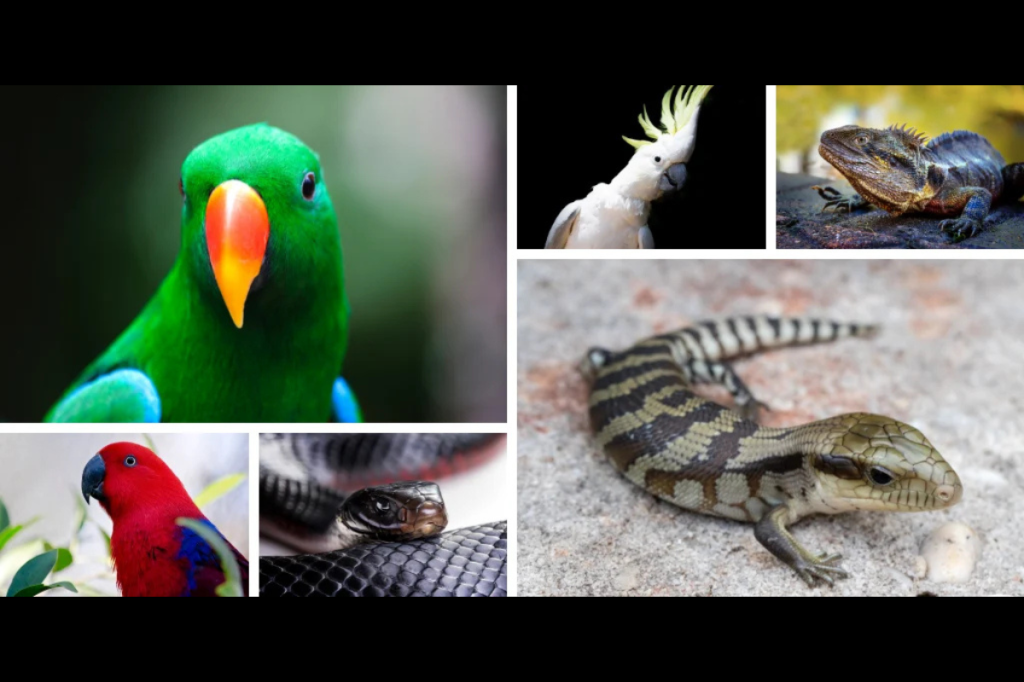

Australia’s unique animals make it a prime target, and reptiles are the most sought after.

Sleepy lizards are especially desirable overseas: hardy, distinctive and not found anywhere else in the world.

Their double-headed look (a tail that mimics their head) and bright blue tongue make them a curiosity in exotic pet markets, while their slow, calm nature makes them easy to steal.

“Sleepy lizards are pretty iconic,” Katie says. “Most people have seen one in the backyard or crossing the road … It shocks people when they learn they’re the most heavily trafficked species leaving Australia.”

A global crime network with roots in SA

The trafficking routes used for Australian reptiles mirror those used for other contraband. Networks source animals locally, move them through transport mules and ship them via hubs such as Hong Kong to buyers in Europe and North America.

Border interceptions represent an estimated 10 per cent of the true scale. Most animals are never detected.

While sleepy lizards are the most popular, other South Australian reptiles are also attractive to traffickers, including invertebrates like Flinders Ranges scorpions, which cannot be bred in captivity. Any for sale are, by definition, illegally wild-caught.

Our native birds, including black cockatoos, are still trafficked too, though at lower rates than in previous decades.

“This isn’t just petty poaching – it’s serious organised crime and it’s harming our wildlife and damaging our environment,” says Nigel Smart, CEO of Crime Stoppers SA.

Stuffed in socks and taped into cartons

This is the part of the trade that horrifies most South Australians. “We see reptiles taped up, immobilised, stuffed into socks and containers,” Katie says. “One case involved someone trying to move 90 sleepy lizards together. They’re solitary animals. The suffering is enormous.”

She says traffickers have no incentive to treat animals humanely because they are worth so much to buyers. “They don’t care if nine out of ten die, because the profit on the one that survives is still enough to make the crime worth it.”

Other cases have involved birds laundered through sham zoos overseas and live freshwater fish smuggled through airports concealed in clothing.

Nigel reinforces that wildlife trafficking is cruelty, plain and simple. “The sad reality is that many die in pain before they are ever sold,” he says.

What happens when species disappear

Removing animals from the wild destabilises ecosystems.

Sleepy lizards eat flowers, berries, insects and snails, disperse seeds and help keep grasslands and gardens healthy. Losing them has compounding impacts – especially because they can live for decades.

“When you start exploiting a species, things get out of whack,” Katie says. “Invasive species are often the first to jump in and fill these gaps, and that causes a whole new set of problems.”

SA’s crackdown

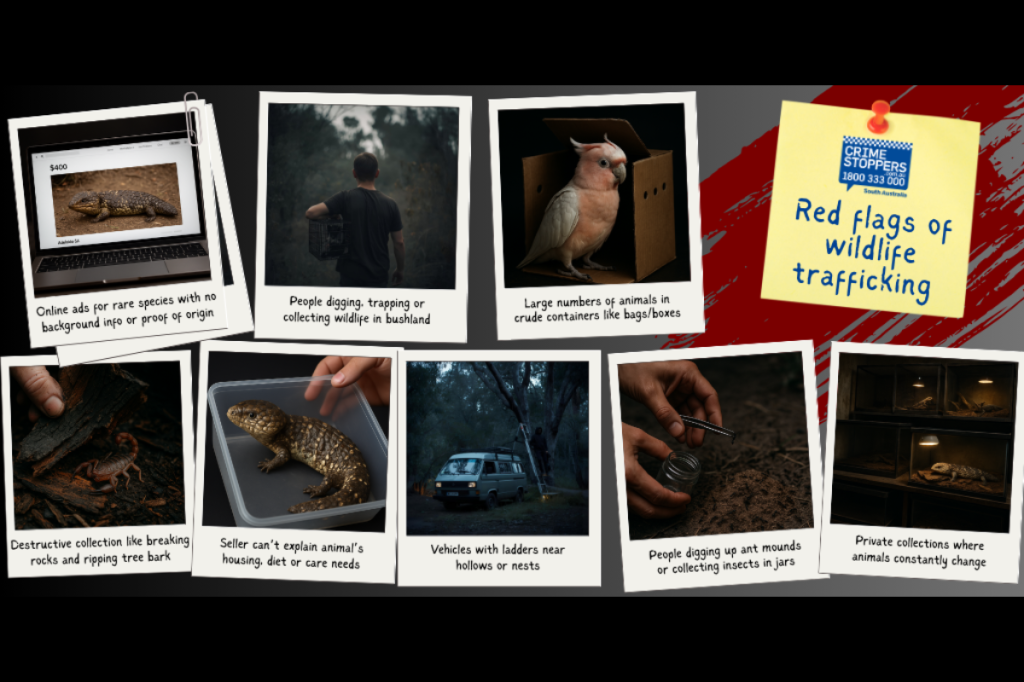

To tackle the issue, the State Government has launched the Call It Out campaign with Crime Stoppers SA, urging people to report suspicious behaviour linked to wildlife trafficking. The campaign outlines key warning signs for hikers, park visitors, regional communities and online shoppers.

It follows the introduction of South Australia’s first Biodiversity Act, which significantly increases penalties for harming or trafficking native animals. Under the Act, individuals face fines of up to $500,000 or 10 years jail.

Katie says the Wildlife Crime Research Hub worked closely with the State Government on aspects of the new Act, helping shape the wildlife-trafficking clauses that hadn’t existed before.

The Hub also supported the development of the Call It Out campaign by helping refine the research-informed ‘red flags’ the public is now being asked to watch for.

“These stronger penalties are crucial,” Katie says. “Illegal wildlife trade is usually a low-risk, high-reward crime. If penalties are low, there’s no deterrent.”

But she says legal reforms alone aren’t enough. “You can’t solve this with one agency… it’s everyone – police, Border Force, state wildlife departments, researchers. It’s a huge network that needs to be involved.”

The SA researchers leading the national fight

South Australia is home to the country’s leading research centre tackling wildlife crime – the Wildlife Crime Research Hub at Adelaide University.

The Hub collaborates with partner organisations around Australia. Its researchers develop tools and technologies to help investigators understand smuggling routes, identify species in the trade and monitor online markets.

“We try to collaborate with everyone – criminal lawyers, rangers, state and federal agencies, NGOs,” Katie says. “Researchers are only one part of the puzzle.”

“There’s real momentum. Australia can be a trailblazer in this space – and a lot of that work is happening right here in South Australia.”

What South Australians can look for

The Call It Out campaign highlights red flags to watch for in parks, reserves and regional areas:

- people digging, trapping or collecting animals

- ladders or gear near tree hollows

- off-track or concealed vehicles

- suspicious insect or plant collection

- anyone handling wildlife without obvious cause

Online, warning signs include:

- listings for native animals without a valid SA permit number

- sellers who can’t explain basic care

- repeated ads for the same species

- unusually cheap prices or vague origins

Nigel says community tips can be critical: “If you see it, call it out”.

Katie agrees: “Small pieces of information can be the missing link that helps investigators stop traffickers”.

And despite the scale of the trade, Katie is optimistic. “We’re seeing awareness grow, we’re seeing law reform, and we’re seeing agencies come to us wanting to work together,” she says. “We’ve got new technology, new partnerships, and a whole community working on this.”

Find out more about wildlife trafficking in SA here, and anonymously share information here.