POTS affects more Australians than epilepsy — yet many GPs don’t know it exists. Meet the South Australian scientist fighting to change that.

It starts with a racing heart. Maybe some dizziness. Then comes the brain fog, the fatigue, the lightheadedness. You look fine – but you can’t stand up. You might even feel like you’re going to die.

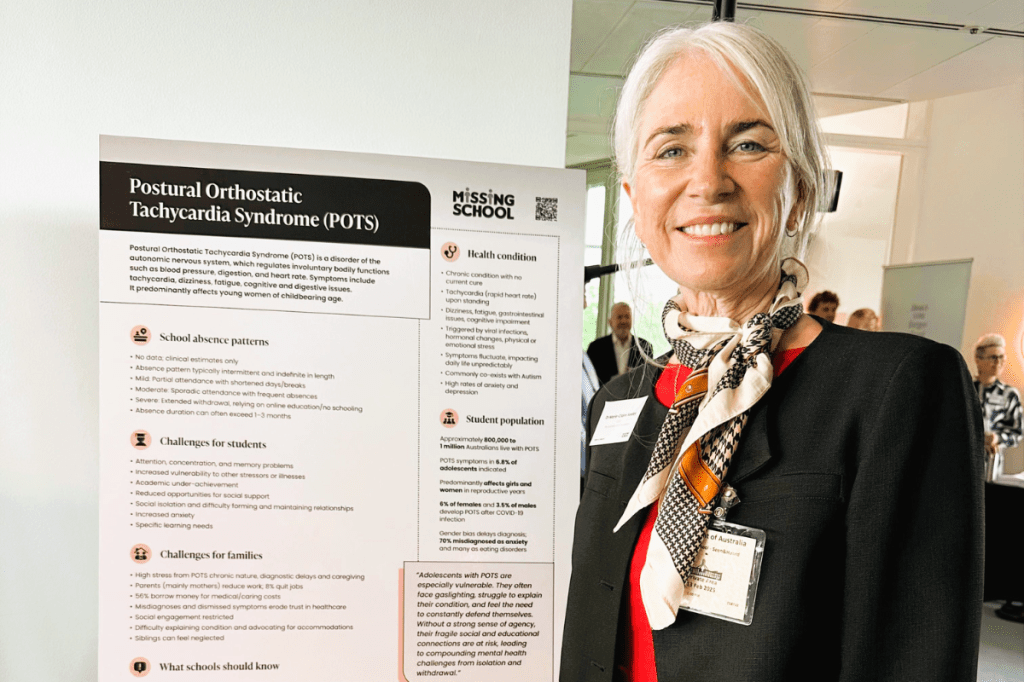

For a growing number of young Australians, especially women, these symptoms aren’t anxiety. They’re not stress. They’re signs of a hidden condition called POTS – short for postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome – a dysfunction of the body’s autopilot nervous system that’s usually triggered by a viral infection, like COVID or glandular fever. That’s why cases have exploded since the pandemic.

And while it affects an estimated 800,000 Australians, many GPs still don’t know what it is. Many mistake it for panic attacks or hormones – leaving young women sick and searching for answers.

From farmgirl to aid worker to patient

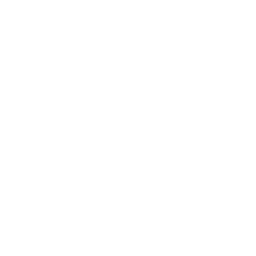

Before she became a Churchill Fellow, a winner in the 2025 South Australian Science Excellence and Innovation Awards and founder of the Australian POTS Foundation, Dr Marie-Claire Seeley was one of those young women who suddenly found herself unable to stand up.

She grew up on a farm – was “tough as boots” – and never imagined she’d one day be flattened by a debilitating illness.

In 1993, while working overseas in the Middle East as a humanitarian aid worker with her husband, she caught a virus. It was the aftermath – the unexplained illness that came next – that changed everything.

“I’d stand up and feel this incredible rush – my vision would go, I felt like I was going to faint,” she says. “My heart rate would hit 200, but every test came back normal.”

At the time, she wasn’t medically trained. Doctors told her husband she was just “an anxious young wife”. Eventually, she returned to Australia, became a registered nurse, and quietly began researching the strange condition she was living with. Eventually, she found its name: POTS.

A disease that’s invisible – and terrifying

People with POTS often look fine from the outside. But on the inside, their bodies are in chaos. Blood pools in their legs, their heart races, they feel dizzy, breathless, and foggy.

Sometimes they faint. Sometimes they don’t – and that’s part of the problem.

“It’s an invisible condition,” Dr Seeley explains. “Unless someone faints, no one can see what’s happening. But the symptoms are terrifying – you feel like you’re going to die.”

Most people with POTS are teenage girls and younger women – about 85 per cent, according to international data – and many are otherwise fit, healthy and high-achieving. Some also have linked conditions like endometriosis, ADHD or hypermobility. Most are used to pushing through pain.

Which makes it all the more devastating when their bodies suddenly stop working – and no one believes them.

“There’s real psychological trauma that comes from being dismissed over and over again,” Dr Seeley says. “People lose their jobs, their relationships, their sense of self – and all the while they’re being told ‘it’s your fault’.”

The long wait for answers

Research shows that around 25 per cent of people with POTS have to stop working or studying because of their symptoms. Over 50 per cent end up in emergency departments multiple times before they’re diagnosed. On average, it takes seven years to get a diagnosis – and women wait far longer than men.

“Many GPs say they don’t know what POTS is,” says Dr Seeley. “And most of those who have heard of it haven’t been trained to diagnose or manage it.”

That’s why her research – and her advocacy – matter so much.

At the University of Adelaide, Dr Seeley completed a PhD examining the overlap between POTS and long COVID. Her research showed that nearly 80 per cent of people with long COVID met the diagnostic criteria for POTS – helping explain why so many are still unwell months after infection.

“A lot of people with long COVID actually have POTS,” she says. “And it’s something we already know how to manage – if we can recognise it.”

Treatable – but not affordable

Once diagnosed, POTS can be managed with the right support: lifestyle adjustments, gradual rehab, and ioften medication. But those medications aren’t currently covered by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme – leaving many patients hundreds of dollars out of pocket each month.

“The average person with POTS pays about $500 a month for medication,” says Dr Seeley. “You basically have to be able to afford private healthcare to be diagnosed and managed – which is not right.”

She calls it a health equity issue. The people most affected are often young, unable to work, and not in a position to advocate for themselves.

“It’s a catch-22. You can’t work because you’re unwell, but you can’t afford treatment unless you’re working.”

Building the system from the inside

In 2021, Dr Seeley founded the Australian POTS Foundation – a volunteer-run organisation now reaching more than 250,000 people a year with their resources. These include information, peer support, and training tools for doctors and allied health professionals.

That work, alongside her PhD research, helped lead to the introduction of Australia’s first official diagnostic code for POTS in mid-2025 – a crucial step in improving recognition, treatment and funding.

“It’s about building the system we need,” she says. “We’re not here to blame doctors – we’re here to give them the tools to help them manage these patients.”

From Adelaide to the world

This year, Dr Seeley was named a winner in the PhD Research Excellence category of the 2025 South Australian Science Excellence and Innovation Awards, run by the SA Government. It’s a recognition she says means a lot – not just for her, but for every patient whose experience has been ignored.

“It’s really special to see this kind of research acknowledged,” she says. “For so long, people with conditions like POTS have felt invisible. Awards like this help shine a light where it’s most needed.”

The SA Science Excellence and Innovation Awards are the state’s premier STEMM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Maths and Medicine) prizes. Run by the Department of State Development, they recognise South Australia’s top individuals and teams across research institutions, schools, industry and the community who are having a significant impact on society, the environment, health, and our economy.

The PhD Research Excellence Award recognises recent PhD graduates who’ve made outstanding contributions and demonstrate strong future potential. It comes with $10,000 in funding and a high-profile platform to help amplify their impact.

She’s also been awarded a Churchill Fellowship, and later this year she’ll travel to leading autonomic research centres overseas – including Stanford, the Mayo Clinic and Vanderbilt – to learn how other countries are training clinicians and managing care.

Her goal is to bring that knowledge home to put to use here.

“South Australia is already a leader in this space. We’ve done the research. We’ve built the foundation. Now we need to build the next step – education, diagnosis and support, so people aren’t falling through the cracks.”

Until then, her message to young people living with POTS is that “if you feel something isn’t right, keep asking questions. You know your body better than anyone else.”

Read about all the 2025 SA Science Excellence and Innovation Awards winners and finalists here.